Encouraging young Australians to better understand and engage with their neighbourhood might be more worthwhile than building a national war cemetery in Canberrra to commemorate the Anzac centenary in 2015, writes John Blaxland.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott is looking to build a landmark to commemorate the centenary of World War I and to build a legacy for his prime ministership.

In doing so, he has backed the creation of an interpretive centre in France. He also has called for an Arlington-like cemetery for Canberra ''in which significant ex-soldiers could be interred''.

Perhaps investing in building closer regional ties that build on our military heritage would be more worthwhile.

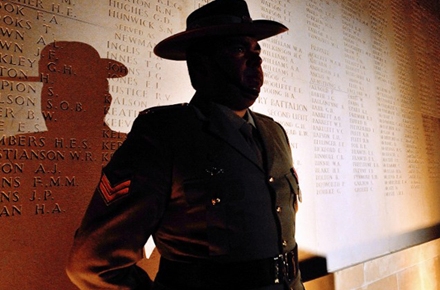

On one level Mr Abbott's ambitions are understandable. After all, Arlington National Cemetery is an evocative and humbling place with the graves of famous and not-so-famous Americans spanning generations overlooking the Potomac River and the National Mall.

This has appeal given Canberra's similarities with the planned city of Washington DC.

No doubt Opposition Leader Bill Shorten does not want to be seen as partisan on an issue like this, so his support is understandable as well.

Yet the comparison with Arlington falls short.

Arlington is but one of a network of more than 100 similar US national cemeteries, allowing Americans to bury their loved ones close to home.

One wonders what West Australians, for instance, would make of this proposal.

The Prime Minister is no doubt sincere in his respect and regard for those who have served the nation in uniform.

But there are compelling reasons why this idea does not translate readily to Canberra and why his commemorative energy should be channelled elsewhere.

First, already more than 102,000 Australian war dead are buried elsewhere.

Until recently, Australians, like their New Zealand, British, Canadian, Indian and South African counterparts, have been buried in Commonwealth war graves alongside the actual battle sites where they fought and died.

As Australians they were equal in life, they are honoured equally in their sacrifice. We should be wary of changing that approach.

At a practical level, the proposal raises some difficult questions. Who is this cemetery for? Who is ''significant''? Who would determine eligibility? Will remains be disinterred from elsewhere and reinterred? Will the cemetery have a religious or secular character? Will the families of veterans be included? Will the more significant have a better class of monument?

If only a few are brought home, how would they be chosen? Solomon would have difficulty adjudicating these questions in contemporary Australia.

We need to remember that we already have such a venue for commemoration - namely the Australian War Memorial, where the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is located.

Washington does not have one memorial for all its wars other than Arlington National Cemetery.

Former prime minister Paul Keating was famous for seeking to reinvent the mythology of Australia's identity, downplaying the significance of Gallipoli and emphasising Kokoda in Papua New Guinea.

His plans arguably fell short because of a partisan approach to something that should unite us.

But he had a valid point about bringing Australia's sense of identity closer to our shores.

Perhaps the best way to build a legacy is for us to look not only at the battles in Europe but those fought closer to home as well.

Such a refocusing of our commemorative efforts could help strengthen ties in the region.

A commemorative centre alongside the Bomana Commonwealth War Cemetery just outside of Port Moresby, for instance, may be a suitable place to build a legacy and to reinforce the ties with our kin in Papua New Guinea.

Such a centre could place Kokoda more centrally in the Australian memory and perhaps de-politicise the commemoration of battles fought in the defence of Papua New Guinea as being something not just identified with one side of politics' interpretation of history, but belonging to all Australians.

The Prime Minister has rightly talked about ''more Jakarta and less Geneva''.

In an effort to build stronger ties, it would be helpful to foster greater understanding of the region by generating increased understanding of the sacrifice made by Australians in south-east Asia and the south-west Pacific.

Indeed Australia has continued its military engagement in this region in the years since the Vietnam War through numerous commitments in Cambodia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, East Timor and beyond; commitments I write about in my new book.

Perhaps as he seeks to invigorate regional ties, Mr Abbott should place emphasis, not on building yet another monument in Canberra, but on remembering where Australians have fought and died in the region, not just in Europe. Perhaps in doing so young Australians also could be encouraged to better understand and engage with their neighbourhood.

Dr John Blaxland is a senior fellow at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, at the Australian National University. His latest book, The Australian Army from Whitlam to Howard, has just been released by Cambridge University Press.