Hard choices for human rights

A commitment to non-intervention could prove one of the biggest stumbling blocks to ASEAN’s efforts to promote human rights, writes MATHEW DAVIES.

ASEAN has come a long way on human rights issues since the mid-1990s, but it still has much further to travel.

Mr Rafendi Djamin, Indonesian Representative to the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) recently spoke at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific on the future of ASEAN’s engagement with human rights.

Mr Djamin highlighted three key areas where ASEAN has made progress on human rights; agenda-setting, the mainstreaming of human rights and including all states in human rights discussions. It is true that each represents an important step towards a region where human rights are more assured.

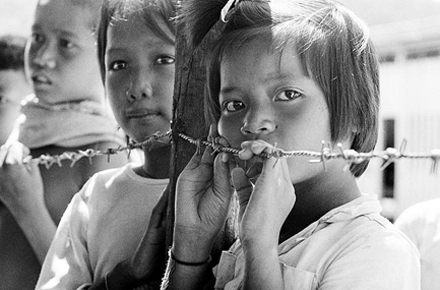

The 2012 ASEAN Human Rights Declaration for the first time created a set of standards across the 10 member states of ASEAN. This joins other regional declarations on the status of women, migrant workers and children to name just three. A comparison with the situation even 10 years ago, let alone 20, shows this to be a substantial forward step.

Areas of traditional ASEAN cooperation, notably in the economic field, are now at least potentially open to input from the AICHR concerning the role of human rights. Mainstreaming human rights promises new ways to develop human rights conversations in ASEAN by revealing how a human rights component promotes economic growth and sustainable development. In areas as diverse as environmental protection, resource management and transnational challenges, a human rights is now observable in ASEAN debates.

The ASEAN human rights dialogue includes 10 diverse states. While often viewed as a negative, Mr Djamin noted that, true to ASEAN’s diplomatic culture, including all states was a price worth paying, especially in the realm of human rights. Whilst this leads to compromise, it also allows consensus to emerge. If every state insisted on an ‘all or nothing’ approach, then there would be no ASEAN at all.

While I share the general optimism of this account, we should not ignore the reality of the situation in ASEAN. When I spoke at the event I highlighted three areas of concern that together reveal a substantial gap between the expectations many have about ASEAN and its ability to deliver real results.

The first challenge is developing coherence in the ever more crowded human rights space in Southeast Asia. How do the separate Commissions on Human Rights and on Women and Children relate to each other? How will ASEAN institutions work with the various United Nations human rights systems that penetrate the region? How will civil society actors work with the emerging ASEAN system?

The strong criticism of the Human Rights Declaration suggests the relationship will be stormy. Many ASEAN states have relatively low levels of bureaucratic capacity to adequately manage these competing demands and it will be important that ASEAN institutions find a positive and separate role to avoid overlap and costly duplication.

The second challenge is to more fully explore the relationship between human rights promotion versus human rights protection. When we talk about promotion we usually mean ‘make the situation better in the future’, whereas human rights protection suggests some sort of mechanism for correcting past wrongs.

ASEAN, in its process of reform over the last 10 years, has often claimed to want to be ‘people-centred’. How will ASEAN be truly people centred if it is unable to make not only the lives of regional citizens yet to be born better, but actually positively impact on the lives of those who are seeking redress from their government?

The third and final challenge concerns ASEAN’s focus on non-intervention. The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, in its last article, states that nothing in the Declaration can be interpreted as undercutting the aims of ASEAN as outlined in the ASEAN Charter.

The charter is clear that the aims of ASEAN include non-intervention, sovereign equality and the right to a national existence free from all external interference.

It remains to be seen how those within ASEAN who wish to push a more active human rights role for the organisation can overcome this commitment, or even whether they actually want to. Continued commitment to non-intervention may be the way to get otherwise reluctant states to agree to human rights within ASEAN, but the price may well be high, weakening regional institutions.

The ASEAN of today has created an ‘opt-in’ system, where states already comfortable with human rights issues can meaningfully participate in a new regional framework of cooperation to complement domestic efforts to promote human rights. This opt-in system, however, can exert only weak and indirect pressure on member states that are unwilling to meaningfully engage in a human rights dialogue.

It is, of course, in these reluctant states that the worst human rights violations have occurred and indeed continue to occur today and so where a strong regional approach is most needed.

Mr Djamin, in his talk, emphasised that the role of human rights in ASEAN is constantly evolving. I agree that the ASEAN of today does not necessarily define the ASEAN of tomorrow.

But if that future ASEAN is to truly commit itself to a people centred approach we will need both real political commitment from the regional elites of today and a willingness to address contentious political issues. Many believe that ASEAN will prove unable to bridge the gap between expectations and its ability to deliver.

It will take the continued active involvement of people such as Rafendi Djamin if ASEAN is to make a meaningful contribution to the human rights situation across Southeast Asia.

Dr Mathew Davies is a research fellow in the Department of International Relations, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific. He researches regional organisations, ASEAN and human rights, and tweets @DrMattDavies.